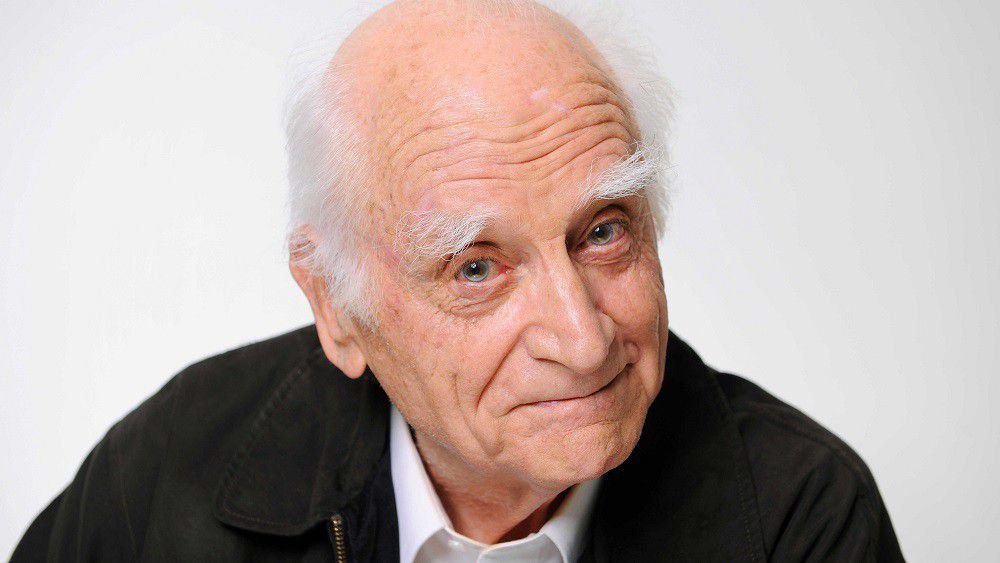

Michel Serres, thèmes importants de sa pensée / Michel Serres, important themes of his thinking

Patrick AULNAS

L’échange, la communication, l’interaction

La pensée de Michel Serres cherche à décloisonner, à établir des passerelles entre des champs cognitifs considérés généralement comme étranger l’un à l’autre. Elle pose également l’échange, la découverte de l’autre, la communication globale comme impératif. De formation à la fois scientifique et philosophique, Michel Serres était bien placé pour appréhender les interactions entre sciences humaines, sciences sociales et sciences de la nature. Depuis l’antiquité, philosophie, géométrie, physique s’enrichissent mutuellement. C’est le lien entre la science, les hommes et le monde qui importe. Relier « cet arbre d’Australie avec l’Aborigène et la biochimie ; le fleuve Garonne avec mon père marinier, ignorant de mécanique des fluides », procure à ce « citoyen du monde » une « liesse quasi religieuse ».

L’analyse de la communication constitue également un élément important. La communication est appréhendée au sens large, celui d’échange : sans échange, pas de vie, pas de société. « Notre corps écoute, crie et se souviens. Bactéries, algues, champignons, plantes et animaux signalent, de même, leur présence et perçoivent l’environnement, chacun à sa façon ; sans ces échanges d’énergie, certes, mais d’information aussi, nul organisme ne survivrait. » L’avènement de l’agriculture, puis, plus récemment, de l’industrie suppose également communication et échange. L’industrie n’a pu se développer que parce que l’humanité disposait d’un moyen efficace de stocker l’information : l’écrit. Aujourd’hui, le développement de l’informatique bouleverse à nouveau le traitement et le stockage de l’information. « Or, issues des actions nécessaires du vivant, et sans doute, plus lointainement de l’inerte, les diverses manières d’accumuler ou d’échanger l’information gouvernent des changements moins visibles mais de plus longue portée que ceux que semblent déterminer les hautes énergies. » Autrement dit, l’impact des « technologies douces », celles qui concernent l’information et la communication (écrit, imprimerie, bibliothèques, informatique), est plus important à long terme que celui des « techniques dures » (mécanique, thermodynamique, etc.). Michel Serres ne croit pas à l’uniformatisation culturelle, crainte souvent exprimée face au développement de la communication planétaire instantanée par le biais des réseaux informatiques. Il reste volontariste et optimiste comme le montre l’extrait suivant :

« J’eus trois passions, l’amour, le savoir et les voyages. J’aime l’étranger, j’aime connaître ailleurs. Bambaras, Zoulous, Amérindiens, Aborigènes, sherpas… je vous ai partout aimés. Nos différences m’enivrent. Aie le courage de construire des ponts à travers les plus durs des chocs culturels. Aucun mot, dans aucun dictionnaire, ne traduit exactement aucun mot de ta langue, leurs aires sémantiques ne correspondent pas. Tu devras donc bégayer un autre langage, tu devras changer de corps à tout degré d’élévation des pôles et à toute longitude. Manger, dormir, parler, marcher, faire signe, ces actes élémentaires demandent l’effort de te lancer de l’autre côté de la rive. Garde la tienne dans ton dos ; tu t’y appuies, tu te reposes sur sa roche, éventuellement tu y trouveras ton repos ; mais tourne sexe, ventre et visage vers l’autre rivage, lance ton arche dans l’échange. Sinon, tu n’apprendras rien. » (L’Art des ponts, Editions Le Pommier, 2006).

La Biogée et le contrat naturel

L’homme des civilisations préindustrielles appartenait au monde naturel et le respectait. Il tirait sa subsistance, jour après jour, de la cueillette, de la chasse, puis de l’agriculture. La révolution industrielle a bouleversé cette relation à la nature : le cartésianisme a conduit l’homme moderne à se croire « maître et possesseur de la nature ». L’homme des civilisations industrielles s’est cru sujet tout puissant du monde-objet : il pouvait y puiser à volonté énergie, matières premières, comme s’il était extérieur au monde, comme s’il ne lui appartenait pas. Or, brusquement, à la fin du 20ème siècle, le monde se rebelle et rappelle à l’homme les limites de sa puissance : pollution, épuisement des ressources naturelles, disparition d’espèces. « Notre culture sans monde retrouve le Monde… Panique ! » Il nous faut désormais introduire un troisième élément dans le « jeu à deux » omniprésent dans la pensée occidentale (sujet-objet, maître-esclave, thèse-antithèse, gauche-droite). Ce troisième élément, Michel Serres l’appelle la Biogée. Le monde, objet d’expérimentation pour les sciences, objet d’exploitation pour les techniques, doit devenir sujet de droit. Il nous faut inventer un nouveau « contrat naturel » dont l’une des parties sera la Biogée, cette « voix du monde » enfin audible. « Retour donc à la nature ! Cela signifie : au contrat exclusivement social, ajouter la passation d’un contrat naturel de symbiose et de réciprocité où notre rapport aux choses laisserait maîtrise et possession pour l’écoute admirative, la réciprocité, la contemplation et le respect, où la connaissance ne supposerait plus la propriété, ni l’action la maîtrise [...] Contrat d’armistice, contrat de symbiose : le symbiote admet le droit de l’hôte, alors que le parasite – notre statut actuel – condamne à mort celui qu’il pille et qu’il habite sans prendre conscience qu’à terme il se condamne lui-même à disparaître. Le parasite prend tout et ne donne rien. Le droit de maîtrise et de propriété se réduit au parasitisme. Au contraire, le droit de symbiose se définit par la réciprocité : autant la nature donne à l’homme, autant celui-ci doit rendre à celle-là, devenue sujet de droit » (Le contrat Naturel, François Bourin, 1990).

Cette nouvelle « voix du Monde » reste à définir sur le plan institutionnel. Qui la représentera ? Michel Serres évoque l’idée de savants qui devraient prêter serment afin de représenter l’air, la terre, les vivants de toutes espèces, la Biogée. Le projet peut paraître utopique, mais tout projet à long terme l’est d’une certaine manière. Une chose est certaine : la vision de Michel Serres ne coïncide pas avec le mouvement écologiste qui ne dépasse en rien les clivages politiques traditionnels, alors que le philosophe ne se positionne ni à droite ni à gauche.

Les objets-monde

La distinction sujet-objet (et sa remise en cause) est une autre dominante de la pensée de Michel Serres. Les objets-monde rendent cette dualité traditionnelle inopérante. « Les artefacts traditionnels, outils et machines, forment des ensembles à rayon d’action local, dans l’espace et le temps : l’alène perce le morceau de cuir, la masse frappe et enfonce le pieu, la charrue taille le sillon… ». Un tel objet est manipulé par un sujet afin d’agir sur d’autre objets voire même parfois sur des sujets. Mais cette relation sujet-objet est nettement délimitée dans l’espace (c’est une relation de proximité immédiate) et le temps (c’est une relation faite de séquences de courte durée). Les objets-monde, au contraire, n’ont plus de limite spatio-temporelle précise. Internet est un réseau global de communication sans limite spatiale claire et sans limite temporelle (il fonctionne continûment). Quel sujet domine cet objet ? La question est sans réponse. Nous sommes en présence d’un objet-monde. Le concept peut être étendu : les effluents gazeux de l’industrie se dispersent dans l’espace de façon incontrôlée, certains déchets nucléaires ont une durée de vie de dizaines de milliers d’années (pas de limite temporelle « humaine »). Ces objets-monde sont incompatibles avec la possession ou la propriété qui suppose une localisation (biens corporels) ou une durée (biens incorporels). Ils ne peuvent pas être traités comme objet au sens classique. « La philosophie classique nous disait naturés ; nous devenons naturants, je viens de le dire : nous faisons naître, au sens étymologique du terme, une toute nouvelle nature, en partie produite par nous et réagissant sur nous. Nous devînmes les hommes que nous sommes pour avoir techniquement sculpté notre environnement, notre maison propre afin de nous protéger ; formée maintenant de ces objets-monde, cette maison évolutive agit désormais sur le monde… » (Hominescence, Editions du Pommier, 2009).

L’hominescence

Ce mot désigne l’évolution fondamentale que vit actuellement l’humanité. Le processus d’hominisation des primates a conduit au développement de l’intelligence. L’homme acquiert une capacité d’action raisonnée sur son environnement. Aujourd’hui, il est confronté à l’action sur sa propre vie (biotechnologies) et il a créé des objets-monde difficilement maîtrisables. Sa créativité lui donne prise sur son évolution future. « Tout dépend de nous. Et par des boucles nouvelles et inattendues, nous finissons nous-mêmes par dépendre de choses qui dépendent globalement de nous. Là, risques et chances croissent aussi vite que notre omnipotence… Comme cela ne nous arriva jamais, nous ne savons pas ce que nous devons faire de tous ces pouvoirs… Ce stade d’hominisation, je le nomme donc hominescence pour en marquer l’importance et pourtant l’adoucir par rapport à d’autres grands moments plus décisifs ; ce mot sonne comme une sorte de différentielle d’hominisation. » (Hominescence, op cit).

Le vieil humanisme a échoué, une autre conscience apparaît

L’homme qui disparaît aujourd’hui avait analysé son environnement, inventé des valeurs, mais sans être capable de les respecter. « Comment cette culture dont nous pleurons la perte n’empêcha ni Rome ni la Grèce de s’écrouler avec un bruit qui retentit encore à certaines oreilles, ni l’Occident qui les remplaça de massacrer des peuples asservis et colonisés, d’exterminer femmes, pauvres, enfants, innocents, plantes, bêtes, ce qui respire et ne respire pas, et, pour finir, de détruire cette même culture dont elle tira cependant, jadis et naguère, sa justification et sa fierté ? Comment ne se sauva-t-elle pas elle-même ? » (Hominescence, op cit).

C‘est ce même humanisme qui a placé les femmes, pendant des millénaires, dans une situation de dépendance parfois proche de l’esclavage. Ecoutons Michel Serres : « Puis-je, enfin et peut-être surtout, garder la moindre confiance dans la sensibilité, la raison, le jugement, la vertu même de ces philosophes, antiques et modernes, de Platon à saint Paul et saint Augustin, de Rousseau et Kant à Schopenhauer, qui, tous et d’une seule voix, prétendent que les femmes, leurs compagnes, évidemment leurs égales, se réduisent, en gros, à des animaux inférieurs ?...Quand ils en excluent la moitié, comment écouter encore leurs bavardages arrogants sur l’humanité ? » (Hominescence, op cit).

Ainsi, nous vivons une crise de conscience, mais « une autre conscience apparaît dès que manque le silence ». Il reste à la philosophie à penser cette autre conscience.

Patrick AULNAS

Exchange, communication, interaction

Michel Serres' thinking seeks to decompartmentalize, to establish bridges between cognitive fields generally considered as foreign to each other. It also sets exchange, the discovery of the other, global communication as an imperative. Michel Serres, who had both a scientific and philosophical background, was well placed to understand the interactions between the humanities, social sciences and the natural sciences. Since antiquity, philosophy, geometry, physics have been mutually enriching. It is the link between science, people and the world that matters. Linking "this Australian tree with the Aborigine and biochemistry; the Garonne River with my father, ignorant of fluid mechanics", gives this "citizen of the world" an "almost religious joy".

The analysis of the communication is also an important element. Communication is understood in a broad sense, that of exchange: without exchange, no life, no society. "Our body listens, screams and remembers. Bacteria, algae, fungi, plants and animals also report their presence and perceive the environment in their own way; without these exchanges of energy, certainly, but also of information, no organism would survive. "The advent of agriculture and, more recently, industry also requires communication and exchange. The industry could only develop because humanity had an effective way of storing information: the written word. Today, the development of information technology is once again disrupting the processing and storage of information. "Now, resulting from the necessary actions of living organisms, and undoubtedly, further away from inert matter, the various ways of accumulating or exchanging information govern changes that are less visible but of longer duration than those that seem to be determined by high energies. "In other words, the impact of "soft technologies", those related to information and communication (writing, printing, libraries, informatics), is greater in the long term than that of "hard technologies" (mechanical, thermodynamics, etc.). Michel Serres does not believe in cultural standardization, a fear often expressed in the face of the development of instant global communication through computer networks. He remains voluntarist and optimistic as shown in the following excerpt:

"I had three passions, love, knowledge and travel. I love foreign countries, I like to know elsewhere. Bambaras, Zulus, Amerindians, Aborigines, Sherpas... I have loved you everywhere. Our differences intoxicate me. Have the courage to build bridges through the hardest of cultural shocks. No word in any dictionary translates exactly any word from your language, their semantic areas do not match. So you will have to stutter another language, you will have to change your body at any degree of elevation of the poles and at any longitude. Eating, sleeping, talking, walking, waving, these elementary acts require the effort of throwing yourself across the shore. Keep yours in your back; you lean on it, you rest on its rock, you will eventually find your rest there; but turn sex, belly and face towards the other shore, throw your ark into the exchange. Otherwise, you won't learn anything. " (L'Art des ponts, Editions Le Pommier, 2006).

Biogée and the natural contract

Man in pre-industrial civilizations belonged to the natural world and respected it. He made his living day after day from gathering, hunting and then farming. The Industrial Revolution disrupted this relationship with nature: Cartesianism has led modern man to believe that he is "master and possessor of nature". The man of industrial civilizations believed himself to be the all-powerful subject of the object-world: he could draw energy and raw materials from it at will, as if he were outside the world, as if he did not belong to it. However, suddenly, at the end of the 20th century, the world rebelled and reminded man of the limits of his power: pollution, depletion of natural resources, extinction of species. "Our culture without a world is back in the world... Panic! "We must now introduce a third element into the "game of two" omnipresent in Western thought (subject-object, master-slave, thesis-antithesis, left-right). Michel Serres calls this third element Biogée. The world, an object of experimentation for science, an object of exploitation for technology, must become a subject of law. We need to invent a new "natural contract" in which one of the parties will be the Biogée, this "voice of the world" that can finally be heard. "So back to nature! This means: to the exclusively social contract, adding the signing of a natural contract of symbiosis and reciprocity where our relationship to things would leave control and possession for admiring listening, reciprocity, contemplation and respect, where knowledge would no longer imply ownership, nor action control [....] Armistice contract, symbiosis contract: the symbiote admits the right of the host, while the parasite - our current status - condemns to death the one he plunders and inhabits without realizing that in the long run he condemns himself to disappear. The parasite takes everything and gives nothing. The right of control and ownership is reduced to parasitism. On the contrary, the right of symbiosis is defined by reciprocity: as much as nature gives to man, so much he must give back to man, who has become a subject of law" (Le contrat Naturel, François Bourin, 1990).

This new "voice of the world" has yet to be defined at the institutional level. Who will represent her? Michel Serres evokes the idea of scientists who should take an oath in order to represent the air, the earth, the living of all species, the Biogée. The project may seem utopian, but any long-term project is in a way utopian. One thing is certain: Michel Serres' vision does not coincide with the ecological movement, which in no way transcends traditional political divisions, while the philosopher does not position himself either to the right or to the left.

World objects

The subject-object distinction (and its questioning) is another dominant feature of Michel Serres' thinking. World objects make this traditional duality inoperative. "Traditional artifacts, tools and machines form units with a local radius of action, in space and time: the awl pierces the piece of leather, the mass strikes and drives the stake, the plough cuts the furrow...". Such an object is manipulated by a subject in order to act on other objects or even sometimes on subjects. But this subject-object relationship is clearly delineated in space (it is a relationship of immediate proximity) and time (it is a relationship made up of sequences of short duration). World objects, on the other hand, no longer have a precise spatial and temporal limit. The Internet is a global communication network with no clear spatial boundaries and no time limits (it operates continuously). Which subject dominates this object? The question is unanswered. We are in the presence of a world object. The concept can be extended: gaseous effluents from industry disperse uncontrolled in space, some nuclear waste has a lifetime of tens of thousands of years (no "human" time limit). These world objects are incompatible with possession or ownership, which implies location (tangible property) or duration (intangible property). They cannot be treated as an object in the classical sense. "Classical philosophy told us that we were natural; we are becoming natural, as I have just said: we are creating, in the etymological sense of the term, a whole new nature, partly produced by us and reacting on us. We became the men we are for having technically sculpted our environment, our own house in order to protect ourselves; now formed from these world objects, this evolving house now acts on the world..." (Hominescence, Editions du Pommier, 2009).

The hominescence

This word refers to the fundamental evolution that humanity is currently undergoing. The process of primate hominization has led to the development of intelligence. Man acquires a capacity for reasoned action on his environment. Today, he is confronted with action on his own life (biotechnologies) and has created world objects that are difficult to control. His creativity gives him a hold on his future evolution. "It all depends on us. And through new and unexpected loops, we end up depending on things that depend on us globally. There, risks and opportunities grow as fast as our omnipotence... As it never happened to us, we don't know what we should do with all these powers... This stage of hominization, I call it hominescence to mark its importance and yet soften it compared to other great more decisive moments; this word sounds like a kind of differential hominization. "(Hominescence, op cit).

The old humanism has failed, another consciousness appears

The man who is disappearing today had analyzed his environment, invented values, but without being able to respect them. "How did this culture, whose loss we mourn, prevent neither Rome nor Greece from collapsing with a noise that still resounds in some ears, nor the West that replaced them from slaughtering enslaved and colonized peoples, from exterminating women, poor people, children, innocents, plants, beasts, that which breathes and does not breathe, and, finally, from destroying the same culture from which it nevertheless drew its justification and pride, then and now? How could she not save herself? "(Hominescence, op cit).

It is this same humanism that has placed women, for millennia, in a situation of dependence that is sometimes close to slavery. Let us listen to Michel Serres: "May I, last but not least, retain the slightest confidence in the sensitivity, reason, judgment and very virtue of these philosophers, ancient and modern, from Plato to Saint Paul and Saint Augustine, from Rousseau and Kant to Schopenhauer, who, all and with one voice, claim that women, their partners, obviously their equals, are reduced, in essence, to inferior animals?...When they exclude half of them, how can they still listen to their arrogant gossip about humanity? "(Hominescence, op cit).

Thus, we are experiencing a crisis of consciousness, but "another consciousness appears as soon as silence is lacking". Philosophy still has to think about this other consciousness.