TARENTULE, TARENTELLE, TARENTATA ET PIZZICA / TARENTULE, TARENTELLE, TARENTATA AND PIZZICA

https://www.youtube.com/embed/RqDjqiCnV80

À voir le nombre d'octogénaires pédaler allègrement sur les routes de campagne du Salento ou vaquer à leurs occupations dans les ruelles de Melpignano, on se dit qu'ils ont dû beaucoup chanter et danser… Melpignano, petit village de 2 200 habitants, forme avec huit autres communes une enclave hellénophone appelée Grecìa Salentina, située à une quinzaine de kilomètres au sud de Lecce.

La population locale parle encore un dialecte grec, connu sous le nom de “griko” ou encore “grecanico”, vestiges de la Grande Grèce de l'Antiquité et de la domination byzantine. Il y a une dizaine d'années, après la grande vague d'immigration qui avait dépeuplé la région dans les années cinquante et face à une Europe qui redessinait ses frontières, les neuf communes ont souhaité réaffirmer leur identité. “Nous avons voulu créer un lien dynamique entre la tradition et l'innovation, non pas en nous renfermant sur nous-mêmes, mais en nous ouvrant sur la nouveauté. Notre volonté était de nous rencontrer, pas de nous affronter”, raconte Sergio Blasi, le maire de Melpignano.

Chaque été depuis 1998, sa ville accueille donc la Notte della Taranta [la Nuit de la Tarente], un mégaconcert gratuit qui vient clore près d'un mois de festival itinérant dédié à la musique populaire des Pouilles et organisé dans les neuf communes de la Grecìa Salentina.

Conformément à la volonté d'ouverture des promoteurs, les musiciens et chanteurs participant au concert sont dirigés par un chef d'orchestre issu d'un genre musical radicalement différent. Ainsi, en 2003, c'est sous la baguette de Stewart Copeland, le batteur de Police, que s'est déroulée la Nuit de la Tarente ou, en 2000, sous celle du jazzman Joe Zawinul, fondateur du groupe Weather Report.

Le chef d'orchestre invité dispose d'un mois pour s'approprier le répertoire traditionnel du Salento et le réinterpréter selon son propre code musical lors du grand concert final. Mais d'autres groupes, comme Buena Vista Social Club, ou d'autres artistes italiens, comme Franco Battiato, Gianna Nannini et Lucio Dalla, sont également invités à participer sur scène aux côtés des chanteurs et des musiciens traditionnels de la région.

“Ce n'est pas un concert au sens classique du terme. C'est plutôt une véritable création, une œuvre originale, une immense fête avec un public qui est tout sauf passif”, commente le maire de Melpignano. Dès l'après-midi, les spectateurs commencent à affluer. Une scène a été dressée sur l'immense pelouse qui s'étend devant la petite église baroque du Carmine datant du XVIIe siècle et l'ancien couvent des Augustiniens.

À la nuit tombée, lorsque les premières notes de tambourins et d'accordéons diatoniques se font entendre, la foule, toutes générations confondues, se retrouve sur les places, dans les ruelles ou dans les maisons pour participer aux réjouissances, pour une gigantesque fête de famille. Le grand-père danse avec sa petite-fille, les couples se défient en un pas de deux amoureux, tandis que les plus solitaires suivent depuis leur salon le spectacle retransmis sur une chaîne de télévision locale.

“C'est là que notre musique traditionnelle reprend son sens premier et nous apporte un remède contre les angoisses véhiculées par le monde moderne et la mondialisation”, observe encore Sergio Blasi. Car la pizzica, dérivée de la tarentelle, une danse et une musique populaires pratiquées dans tout le Sud de l'Italie, est née, en effet, pour guérir. Elle est directement liée au tarentisme, un rituel de guérison mêlant danse, musique, transe, possession et dévotion chrétienne, dont l'existence est documentée dès le XIVe siècle. Mais celui-ci aurait des origines bien plus anciennes puisque certains n'hésitent pas à le rapprocher des rites dionysiaques de l'Antiquité.

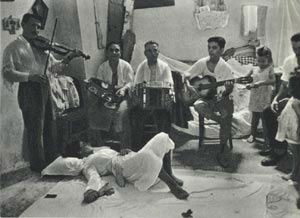

Ce rituel était censé guérir les personnes, des femmes pour la plupart, qui avaient été piquées par la tarentule ou lycosa tarantula, une araignée très répandue dans la région. Les victimes – les tarantate – étaient alors frappées d'hystérie, secouées de convulsions ou, au contraire, plongées dans une profonde léthargie. Pour se libérer de l'emprise de l'araignée qui vivait en elle, la tarantata n'avait d'autre choix que de danser jusqu'à épuisement sur le rythme effréné de la pizzica exécutée par des chanteurs à la voix nasillarde et haut perchée et des joueurs de tambourins, de violons et d'accordéons diatoniques.

Les musiciens adaptaient leur “traitement” en fonction de l'espèce de la tarentule qui avait piqué la victime. Selon le type de venin, la tarantata avait un comportement agité, mélancolique, agressif ou licencieux. Ils avaient alors recours à des rubans de couleur et des rythmes différents. Ces cérémonies pouvaient durer plusieurs heures, voire plusieurs jours, durant lesquels la victime passait par des phases de transe et d'extase. Ensuite, Saint-Paul, protecteur des pizzicati [“piqués” en italien] et particulièrement vénéré dans une église de la ville de Galatina, dans le Salento, finissait par exorciser le mal.

Les spécialistes de nombreuses disciplines, depuis l'anthropologie médicale à l'ethnopsychiatrie, se sont penchés sur ce bel exemple de syncrétisme culturel pour tenter d'en analyser les multiples origines et significations. D'aucuns y voient une façon de contourner le rigorisme de l'Église catholique du XVIIe siècle en matière de musique et de danse et de perpétuer des rites d'origine païenne.

D'autres y trouvent une explication purement médicale : en accélérant le rythme cardiaque et en libérant des endorphines, cette danse frénétique favorisait l'élimination du venin dans le sang et diminuait la douleur provoquée par la morsure de l'araignée. Aujourd'hui, si le tarentisme a pratiquement disparu, la pizzica, elle, connaît un renouveau indéniable, comme en témoignent le succès de la Nuit de la Tarente et l'énorme popularité des artistes originaires des Pouilles en général et du Salento en particulier.

Les films et les documentaires qui lui sont consacrés sont désormais légion, depuis Sangue Vivo d'Edoardo Winspeare à Il Sibilo lungo della Taranta de Paolo Pisanelli, retraçant son histoire des années soixante à nos jours. Dans ce dernier documentaire, Giovanni Lindo Ferretti, un artiste d'Italie du Nord ayant participé à plusieurs éditions du festival de Melpignano, affirme : “Derrière la musique traditionnelle du Salento se cache une merveilleuse poésie, d'une élégance incroyable, capable de parler à tous les êtres humains, et pas seulement aux Salentins”.

Une poésie écrite par des gens simples et dignes, des paysans qui ont toujours travaillé dur et connu la faim, mais qui n'ont jamais cessé de chanter leurs joies et leurs peines. Un peuple qui aime danser et faire la fête et a trouvé dans la musique son antidote aux venins de l'existence.

Régine Cavallaro

Seeing the number of octogenarians pedalling happily on the country roads of Salento or going about their business in the alleys of Melpignano, it is said that they had to sing and dance a lot... Melpignano, a small village of 2,200 inhabitants, forms with eight other municipalities a Greek-speaking enclave called Grecìa Salentina, located about fifteen kilometres south of Lecce.

The local population still speaks a Greek dialect, known as "griko" or "grecanico", vestiges of Greater Greece from antiquity and Byzantine domination. About ten years ago, after the great wave of immigration that had depopulated the region in the 1950s and faced with a Europe that was redrawing its borders, the nine municipalities wanted to reaffirm their identity. "We wanted to create a dynamic link between tradition and innovation, not by closing ourselves in on ourselves, but by opening ourselves to newness. Our desire was to meet each other, not to confront each other," says Sergio Blasi, Mayor of Melpignano.

Every summer since 1998, his city has hosted the Notte della Taranta[Night of the Taranto], a free megaconcert that ends almost a month of a travelling festival dedicated to popular music from Puglia and organized in the nine municipalities of Greece's Salentina.

In accordance with the promoters' desire for openness, the musicians and singers participating in the concert are conducted by a conductor from a radically different musical genre. Thus, in 2003, the Taranto Night took place under the baton of Stewart Copeland, the drummer of the Police, or in 2000, under the baton of jazzman Joe Zawinul, founder of the group Weather Report.

The guest conductor has one month to appropriate the traditional Salento repertoire and reinterpret it according to his own musical code during the final concert. But other groups, such as Buena Vista Social Club, or other Italian artists, such as Franco Battiato, Gianna Nannini and Lucio Dalla, are also invited to participate on stage alongside the region's traditional singers and musicians.

"This is not a concert in the classical sense of the word. It is rather a real creation, an original work, a huge celebration with an audience that is anything but passive," commented the mayor of Melpignano. In the afternoon, the spectators began to flock. A scene has been erected on the huge lawn in front of the small 17th century Baroque Carmine church and the former Augustinian convent.

At nightfall, when the first notes of tambourines and diatonic accordions are heard, the crowd, of all generations, gather in the squares, in the alleys or in the houses to participate in the celebrations, for a huge family celebration. The grandfather dances with his granddaughter, the couples challenge each other in a single step, while the most lonely follow the show from their living room, broadcast on a local television channel.

"This is where our traditional music takes on its original meaning and provides us with a remedy against the anguish of the modern world and globalization," says Sergio Blasi. Because pizzica, derived from tarantella, a popular dance and music practiced throughout southern Italy, was born to heal. It is directly linked to tarantism, a healing ritual combining dance, music, trance, possession and Christian devotion, whose existence is documented since the 14th century. But this one would have much older origins since some do not hesitate to bring it closer to the Dionysian rites of Antiquity.

This ritual was supposed to heal people, mostly women, who had been bitten by tarantula or lycosa tarantula, a spider that is very common in the region. The victims - the tarantate - were then struck by hysteria, shaken by convulsions or, on the contrary, plunged into a deep lethargy. To free herself from the grip of the spider that lived in her, the tarantata had no choice but to dance to the frantic rhythm of the pizzica performed by singers with a nasal and high perched voice and diatonic tambourines, violins and accordion players.

The musicians adapted their "treatment" according to the species of tarantula that had stung the victim. Depending on the type of venom, tarantata had restless, melancholic, aggressive or licentious behaviour. They then used ribbons of different colours and rhythms. These ceremonies could last several hours or even several days, during which the victim went through phases of trance and ecstasy. Then, St. Paul, protector of pizzicati[Italian for "piqués"] and particularly venerated in a church in the city of Galatina, in the Salento, ended up exorcising evil.

Specialists in many disciplines, from medical anthropology to ethnopsychiatry, have examined this fine example of cultural syncretism in an attempt to analyze its multiple origins and meanings. Some see it as a way of circumventing the 17th century Catholic Church's rigorousness in music and dance and perpetuating pagan rites.

Others find a purely medical explanation: by accelerating the heart rate and releasing endorphins, this frenetic dance promoted the elimination of venom in the blood and reduced the pain caused by the spider's bite. Today, if Tarantula has practically disappeared, pizzica is undergoing an undeniable revival, as shown by the success of Taranto Night and the enormous popularity of artists from Puglia in general and Salento in particular.

There are now many films and documentaries about him, from Edoardo Winspeare's Sangue Vivo to Paolo Pisanelli's Il Sibilo lungo della Taranta, retracing his history from the 1960s to the present day. In this latest documentary, Giovanni Lindo Ferretti, a Northern Italian artist who has participated in several editions of the Melpignano Festival, states: "Behind the traditional music of Salento lies a wonderful poetry, of incredible elegance, capable of speaking to all human beings, and not only to the Salentines".

A poetry written by simple and dignified people, peasants who have always worked hard and experienced hunger, but who have never stopped singing their joys and sorrows. A people who love to dance and celebrate and have found in music their antidote to the venom of existence.

Régine Cavallaro